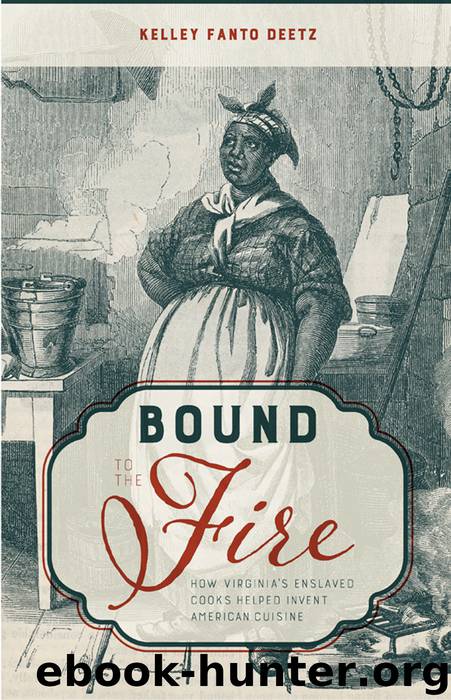

Bound to the Fire by Kelley Fanto Deetz

Author:Kelley Fanto Deetz

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: The University Press of Kentucky

Published: 2017-04-08T04:00:00+00:00

NOTORIOUS POISONERS

While Hercules and Hemings were gaining fame, other enslaved cooks were inciting fear among the southern white elite, as tales of poisoning spread though their circles. West African healers were commonly used by both blacks and whites in colonial and antebellum Virginia. Enslaved cooks were often given the task of mixing certain medicines, such as tonics, that were used by white families. The difference between medicine and poison is dosage, and as a result, many cooks and healers found themselves “poisoning” folks both intentionally and unintentionally. By 1748, Virginia had passed a law stating, “if any negroe, or other slave, shall prepare, exhibit, or administer any medicine whatsoever, he, or she so offending, shall be adjudged guilty of felony, and suffer death without benefit of clergy.”39 There were exceptions to this rule, as many Virginia families relied on and trusted their healers and cooks to administer such medicines. One might assume that poisoning was more commonly done by women; however, between 1705 and 1865, only 15 percent of these enslaved convicts (18 of 118) were women. Ten of them likely acted alone, while eight had male accomplices.40

In addition to making medicines, cooks were responsible for making salves, ointments, remedies, and other household products such as ammonias and dyes.41 Salve was made by taking “mutton suet[,] turpentine, barren soil, melobonet, parsley, elder bark, Night Shade, and bees wax and adding a little honey and brown sugar to it over a slow fire.” Similarly, “mouth water” was made by “tak[ing] Pine Buds, Spanish Oak bark, Alder bark, Persimmon bark, and Sage, boil it in a Bell Metal in weak vinegar, after it boils well take out the ingredients and add Allum Salt Petre and Honey [and] simmer it over a slow fire until its a Syrup.” Ointments were made with “lavender[,] Sassafras Bark[,] Chamomile Feather[,] free Mullen Buds & Sage, a pound of Lard to a half pint of Brandy[.] Simmer it over a slow fire, when the strength is sufficient pour off the Herbs, ring them dry[.] [T]his ointment will keep a year or two—get the ingredients in August.”42

Because they practiced the art of medicinal creation, enslaved cooks had knowledge of and access to poisons such as deadly nightshade and belladonna.43 Their position of trust as the feeders and nourishers of the plantation household made for a very tangled power relationship. It is also essential to note that the majority of enslaved Afro-Virginians were Igbo who had brought their knowledge of both poisoning and foodways with them from Africa.44 Igbo were well known for their understanding of herbs and poisons, as well as their familiarity with supernatural powers. Historian Douglas B. Chambers argues that “the use of poison especially evokes a different matrix of meaning rooted in African conceptions of efficacy.”45

The first record of an enslaved person being convicted of poisoning refers to a woman named Eve. On August 19, 1745, Eve successfully poisoned her enslaver, Peter Montague of Orange County, by polluting his milk. She pleaded not guilty but

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15320)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14473)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12360)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(12080)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12009)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(5757)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5421)

Perfect Rhythm by Jae(5390)

American History Stories, Volume III (Yesterday's Classics) by Pratt Mara L(5292)

Paper Towns by Green John(5171)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(4990)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4944)

The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World by Nathaniel Philbrick(4482)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4477)

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann(4431)

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(4381)

Too Much and Not the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose(4324)

The Borden Murders by Sarah Miller(4302)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4181)